A Colorado River Overview:

Education, Facts & Statistics

From its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to its end at the Gulf of California, the Colorado River defines life in the American Southwest.

Colorado River 101

- Consumptive Use: Water use that does not return to the river is called consumptive use. One example is the water “consumed” by plants to grow. That water does not return to the river through the soil, because the plant has used it. An example of non-consumptive use could be most of the water that a person uses when taking a shower. The water that goes down the drain can be reclaimed, re-treated, and reused.

- Groundwater: Water located beneath the Earth’s surface within aquifers, interacting with and supplying the Colorado River and its tributaries.

- Headwaters: The upper reaches and smaller streams in the Rocky Mountains of the Upper Basin States (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico) that form the initial sources of the Colorado River and its tributaries.

- Law of the River: A complex set of agreements, treaties, court decisions, and regulations that govern the allocation and use of water resources in the Colorado River Basin.

- Lee Ferry: The geographic point on the main stem of the Colorado River, one mile below the mouth of the Paria River in Arizona, where the Colorado River Basin is divided into the Upper Basin and Lower Basin. This location, as defined in the 1922 Colorado River Compact, is where the amount of water that flows from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin is measured.

- Lee’s Ferry: This historic ferry crossing was established in 1873 by John D. Lee. It was a literal ferry — a boat system to get settlers across the Colorado River in a remote area of Arizona. It is now where people launch their boats to head down the Colorado River. A stream gauge was installed at Lee’s Ferry in 1921.

- Lees Ferry Streamgauge: Installed in 1921 at Lee’s Ferry, the Lees Ferry gauge, as well as a streamgauge on the Paria River, are used as measurement points.

- Lower Basin: A geographic boundary for the lower portion of the Colorado River Basin, which includes parts of Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. Lower Basin is often used to refer to the Lower Division States of Arizona, California, and Nevada.

- Mainstem: The primary channel of the Colorado River as it flows from its headwaters in the Upper Basin southwestward towards the Gulf of California.

- Return flows: Water that has been diverted from the Colorado River system for use (e.g., irrigation, municipal) and then returns to the river or its tributaries at a later date.

- Surface water: Water flowing or stored above ground in the Colorado River.

- Tributaries: Smaller rivers and streams (e.g., Gunnison, San Juan, Green) that flow into and contribute water to the main stem of the Colorado River.

- Upper Basin: A geographic boundary for the upper portion of the Colorado River Basin, which includes parts of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. Upper Basin is often used to refer to the Upper Division States of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

1,450

Miles Long

7

States

40M

People Affected

30

Tribes

80%

Agricultural Use

Overview of the Colorado River

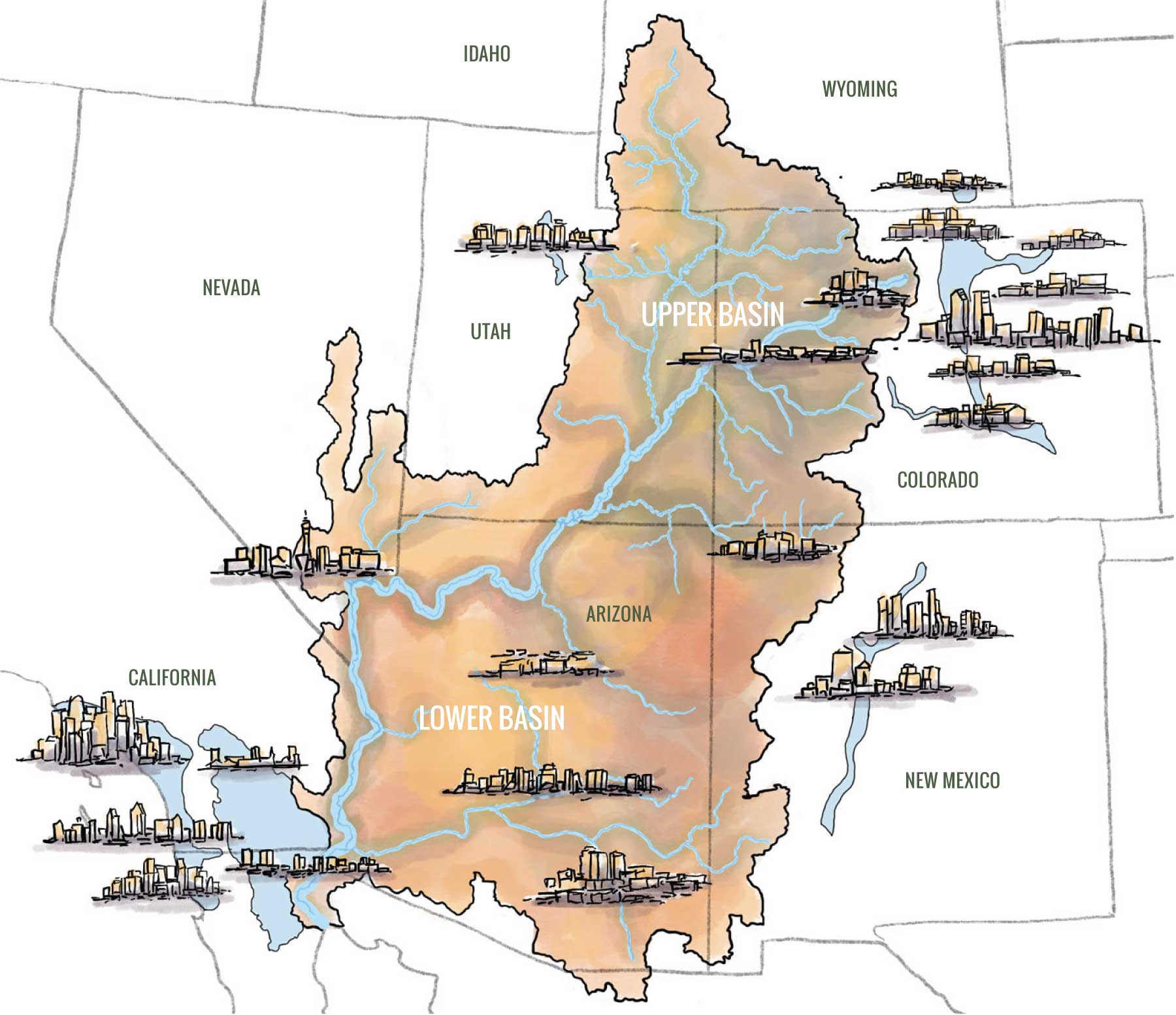

The Colorado River Basin encompasses a vast and geographically diverse area of approximately 250,000 square miles in the southwestern United States.

The Colorado River flows for about 1,450 miles from the high elevations of the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California in Mexico.

The Basin is divided at Lee Ferry, Arizona, located one mile downstream of the confluence of the Paria River and the Colorado River. There, the Colorado River is divided into the Upper Basin, which includes Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming (the Upper Division States), and the Lower Basin, which includes Arizona, California, and Nevada (the Lower Division States). A small portion of Arizona is in the geographic Upper Basin, and a small portion of Utah and New Mexico is in the geographic Lower Basin. The river and its tributaries are a vital water source for these seven states and also serve parts of Mexico.

Within the Colorado River Basin are 30 federally recognized Tribal Nations, each with distinct histories and cultural ties to the region and its waters. These Tribal Nations hold significant water rights within the basin, some of which are the most senior.

Today, the Colorado River Basin is a system. There are numerous reservoirs and infrastructure projects along the river, many built by the federal government in the previous century. The two largest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, are important for water storage and security, and are central to water management in the basin.

Lake Mead, created by Hoover Dam and located on the Arizona-Nevada border, is the largest reservoir in the United States by maximum water capacity. It serves as a major water storage facility for the Lower Basin States, Tribal Nations, and Mexico.

Lake Powell, created by Glen Canyon Dam and located on the Utah-Arizona border, is the second-largest reservoir by maximum water capacity in the United States. Lake Powell plays a critical role in regulating water flow from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin.

Laws that Shape the River

The Colorado River Basin is a complex system governed by a collection of laws, agreements, and decrees known as the Law of the River. Balancing the water needs of the various states, tribes, and Mexico, especially in the face of changing hydrology and climate change, presents new challenges for the southwest region.

What is a Compact?

An interstate compact is a legally binding agreement established between two or more states. This mechanism is authorized by Article I, Section 10 of the United States Constitution.

Interstate compacts hold unique significance. When Congress authorizes a compact, the federal government effectively cedes a portion of its sovereign authority to the participating states, allowing them to govern specific matters through mutual agreement. This authority is derived from the Constitution, enabling states, as sovereign entities, to collaborate on shared concerns and establish legally enforceable agreements among themselves.

1922 Colorado River Compact

The Colorado River Compact holds the distinction of being the first interstate water compact in the United States.

In 1922, following a decade of unusually high precipitation, the seven Basin States of the Colorado River drafted the Colorado River Compact. This agreement allocated 7.5 million acre-feet (one acre-foot is a unit of volume of water needed to cover one acre of land to a depth of one foot, which is equal to 325,851 gallons) of water annually to the Upper Basin States and 7.5 million acre-feet annually to the Lower Basin States, as well as an additional 1 million acre-feet annually to the Lower Basin States for tributary uses that occur in the Lower Basin.

Subsequently, a U.S.-Mexico treaty allocated an additional 1.5 million acre-feet per year to Mexico (see Mexico Treaty section).

A key provision of the Colorado River Compact is Article III(d), which provides that the Upper Division States will not cause the flow of the Colorado River at Lee Ferry to be depleted below 75 million acre-feet for any ten consecutive-year period.

Mexico Treaty

This international agreement allocates Mexico an annual 1.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River system. It also allocates water on the Tijuana River and Rio Grande.

The treaty includes provisions for reduced water allotments to Mexico during periods of extraordinary drought, although the specific criteria defining such conditions are not explicitly outlined within the document.

The International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) facilitates the implementation and management of this treaty. Subsequent “Minutes” issued by the IBWC clarify and provide further detail regarding the implementation of the treaty. These Minutes address specific operational aspects and interpretations, but do not alter the fundamental terms established in the original treaty.

1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact

The primary purpose of the 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact was to apportion the Colorado River water allocated to the Upper Basin states under the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

The apportionment is defined as a percentage of the total water supply available in a given year. The allocations of available supply are:

- Colorado – 51.75%

- New Mexico – 11.25%

- Utah – 23%

- Wyoming – 14%

The Upper Colorado River Commission (UCRC) is an interstate administrative agency established by the 1948 Upper Basin Compact. This agency is unique because the obligations outlined in both the Colorado River Compact and the Upper Basin Compact are shared among the Upper Division States.

The UCRC undertakes various activities to facilitate the administration of the interstate compact, including but not limited to:

- Establishing rules and regulations for compact implementation

- Forecasting water runoff in the Colorado River and its tributaries

- Conducting cooperative studies of the Colorado River System’s water supplies

- Collecting and reporting data on streamflows, storage, diversions, and water use within the tributaries of the Upper Basin

- Making findings regarding flows at Lee Ferry

- Making findings regarding the necessity and extent of curtailment (the action of reducing or restricting water use), if required

It is important to note that the UCRC does not control the in-state administration of water rights, which remains the responsibility of the individual states.

The “Big Three” Today

These three foundational documents, along with subsequent laws, agreements, and judicial decrees, collectively form what is known as the Law of the River (LoR). This body of legal instruments seeks to balance the need for certainty in water resource planning with the flexibility required to adapt to evolving conditions within the Colorado River Basin.

Opportunities continue to exist within the current legal framework to find flexible solutions for addressing contemporary challenges, such as drought and climate change, for present and future generations.

Other Foundational Documents

Beyond the “Big Three” compacts and treaty, several federal laws and a significant t decree have played a crucial role in shaping the management of the Colorado River. These include:

- Winters Doctrine (1908 Supreme Court Case):

This Supreme Court Case established that Tribal water rights are created, even if not explicitly stated. This gave Tribal Nations a legal basis to claim federal reserved water rights, often with senior priority dates. - The 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act:

This act ratified the Colorado River Compact and authorized the construction of Hoover Dam, creating Lake Mead. - The 1956 Colorado River Storage Project Act:

This legislation authorized the development of major water storage facilities in the Upper Basin, including the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam (forming Lake Powell), Flaming Gorge Dam in Utah, Navajo Dam in New Mexico, and the Aspinall Unit dams, Crystal, Blue Mesa and Morrow Point, in Colorado. It also facilitated numerous participating projects, many of which are located in Colorado. - The 1963 U.S. Supreme Court Decision in Arizona v. California and subsequent 1964 Decree:

This landmark decision apportioned the mainstem waters of the Lower Basin among the States of Arizona, California, and Nevada. The Court also affirmed that all mainstem waters in the Lower Basin are under the control of the United States and settled water rights to the mainstream of the Lower Colorado River for five Tribal Nations. The decision and decree do not interpret the Compact. - The 1968 Colorado River Basin Project Act:

This act authorized the Central Arizona Project and established the order of priority for water releases from Lake Powell to meet authorized purposes. It also authorized storage in Lake Powell to help the Upper Division States manage through critical drought periods without harming uses in the Upper basin pursuant to the Colorado River Compact.

Where the Water Comes From

The Colorado River originates high in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, which act as a natural wintertime reservoir, accumulating significant amounts of snowpack. Once spring arrives and temperatures rise, the accumulated snow melts into countless small streams. These little waterbodies gradually converge into larger streams and rivers.

These smaller rivers and streams, fed by snowmelt and precipitation within the Upper Basin, eventually form the mainstem of the Colorado River. Prominent tributaries (a river or stream flowing into a larger river or lake) such as the Gunnison, Dolores, Green, and San Juan Rivers in the Upper Basin, join the Colorado River mainstem to contribute the vast majority of the river’s overall flow.

The Rocky Mountain snowpack is the fundamental source of the Colorado River’s water. Winter snowfall and spring runoff are the natural cycle that has shaped the Colorado River and continues to provide its water supply.

Where the Water Goes

The Colorado River serves as a critical water source for seven states in the southwestern United States: Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming in the Upper Basin, as well as Arizona, California, and Nevada in the Lower Basin. The Colorado River Basin is also home to thirty federally recognized Tribal Nations who rely on the river in various ways. For more information, please see the Tribal Nations resources page.

The allocation and use of this water are governed by a complex framework of laws, agreements, and decrees known as the Law of the River (see descriptions above). Due to the intricate nature of water rights, environmental factors like drought and the variability of the river’s flow, precise, real-time breakdowns of use by sector, geography, location, and exact quantity are challenging to provide in a static format.

Roll over the points on the map to learn more about water is used in state and Tribal Nations.

how the water is used

Agriculture

consistently emerges as the largest single user of Colorado River water across the Basin.

Municipal & industrial

demands are steady and growing throughout the Basin.

Environmental & recreational flows

are increasingly recognized as important uses.

Tribal water rights

are part of the allocations to the states and often senior to non-Tribal water rights. In many states, Tribal water rights are not yet fully developed.

Managing Water in the Upper Basin

The Upper Colorado River Basin States – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming – face unique challenges in managing their share of the Colorado River. The Colorado River begins as snowpack, which follows a natural runoff pattern and can be unpredictable. Additionally, the Upper Division States have complex legal systems for administering how water can be used.

Prior Appropriation:

The Prior Appropriation Doctrine is a system for administering water, common in the drier western United States. It dictates that the right to use water is acquired by the first person to put it to a beneficial use – often summarized as “first in time, first in right.” This creates a hierarchy of water rights based on the date of use, called appropriation. In times of limited water supply, those with the oldest (“senior”) water rights have a higher priority and are entitled to their full allocation before those with more recent (“junior”) rights receive any water. This system contrasts with riparian water rights, common in the eastern U.S., which tie water rights to land ownership adjacent to a water body.

The administration of the prior appropriation system in Upper Division States is the responsibility of each state’s State Engineer. During periods of water scarcity, the State Engineers administer diversions based on the priority dates of water rights. Junior water rights may be curtailed or shut off entirely to ensure that senior water rights receive their full decreed amount.

Sometimes, the stream doesn’t have enough water to give every water right holder the amount of water that they’re legally allowed to use. So when a senior user makes a “call,” they effectively tell the state water officials, “Shut off the junior water users upstream—I need my full amount first.”

Below is a map of active calls in Colorado. Calls for water are more common in the irrigation season (spring, summer, fall) and less common in the winter.

Challenges of Water Management in the Upper Basin

Managing water in the Upper Division States presents several key challenges:

- Hydrologic Variability and a Reliance on Snowpack: Unlike the Lower Basin States, which can rely on stored water in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the Upper Basin’s primary “reservoir” is annual snowpack. This natural water supply is highly variable from year to year. A dry winter can lead to significantly reduced streamflows, directly impacting water availability for all users within a sub-basin. Upper Basin users cannot draw upon stored water from a large reservoir in years with poor snowpack.

- Sub-Basin Hydrology Varies: Each sub-basin within the Upper Colorado River Basin can experience vastly different hydrologic conditions in a given year. One area might have average or even above-average snowpack and runoff, while a neighboring sub-basin could be facing severe drought. Water availability can vary significantly across relatively short distances within a single state.

- Prior Appropriation in Action: The prior appropriation system, while providing a legal framework, means that in dry years, junior water rights holders may receive little to no water. This means that Upper Basin water users must live within their means and may seek other sources of supply in times when they cannot divert their water rights or be curtailed by the State Engineer. Frequently, water dates predating the 1922 Colorado River Compact may be curtailed.

- Limited Storage Capacity: Compared to the massive reservoirs available to the Lower Basin, individual water users and districts in the Upper Basin generally have smaller storage facilities, if any at all. This limits their ability to buffer against fluctuations in water supply within a given year. When streamflows decline in late summer, many water users cease diversions.

- Growing Demands and Climate Change: Like the Lower Basin, the Upper Division States are facing increasing demands for water. Climate change is exacerbating the challenge by contributing to decreased snowpack, earlier runoff, reduced runoff, and prolonged drought conditions.

Managing Water in the Lower Basin

Water management in the Lower Colorado River Basin – Arizona, California, and Nevada – differs significantly from the Upper Basin due to the Lower Basin’s ability to order water from Lake Mead. Unlike the direct diversions from the river that are common in the Upper Basin, the Lower Basin primarily receives their Colorado River water through a system of orders and deliveries via contracts with the federal government.

Colorado River Orders and Delivery

Each Lower Basin water user with a contract for water delivery from Lake Mead submits annual orders to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) specifying the amount of water they request. These orders are then fulfilled by releases from Lake Mead, which is managed by the Secretary of the Interior through Reclamation. The water is delivered through a network of canals and pipelines, often traversing long distances to reach agricultural fields and urban centers.

Role of the Federal Government in Managing the Colorado River in the Lower Basin

The federal government plays a substantial role in managing the Colorado River in the Lower Basin. The federal government’s authority is exercised through the operations of dams and reservoirs, such as Lake Mead, and through the administration of water contracts. The Secretary of Interior is responsible for administering the allocations of Colorado River water among the Lower Basin contractors as defined by the Law of the River and court decrees. This includes approving water delivery contracts and managing releases from Lake Mead.

The Secretary of the Interior plays a crucial role in managing the Colorado River in the Lower Basin, and is often referred to as the “Water Master.”

In essence, the Secretary of the Interior acts as the federal steward of the Colorado River in the Lower Basin, ensuring that the complex system of entitlements and deliveries operates in accordance with federal law and the Law of the River. This role is particularly important in managing the river during periods of drought and shortage, requiring difficult decisions that balance competing water demands.

Climate Change in the Colorado River Basin

Climate change and prolonged drought are significantly altering the hydrological realities of the entire Colorado River Basin, impacting both water supply and demand across the Upper and Lower Basins.

Throughout the Colorado River Basin, climate change is resulting in reduced snowpack, increased evapotranspiration, and altered precipitation patterns.

Reduced Snowpack

Increased Evapotranspiration

Altered Precipitation Patterns

Impacts of the Mega-Drought Over the Last 20 Years

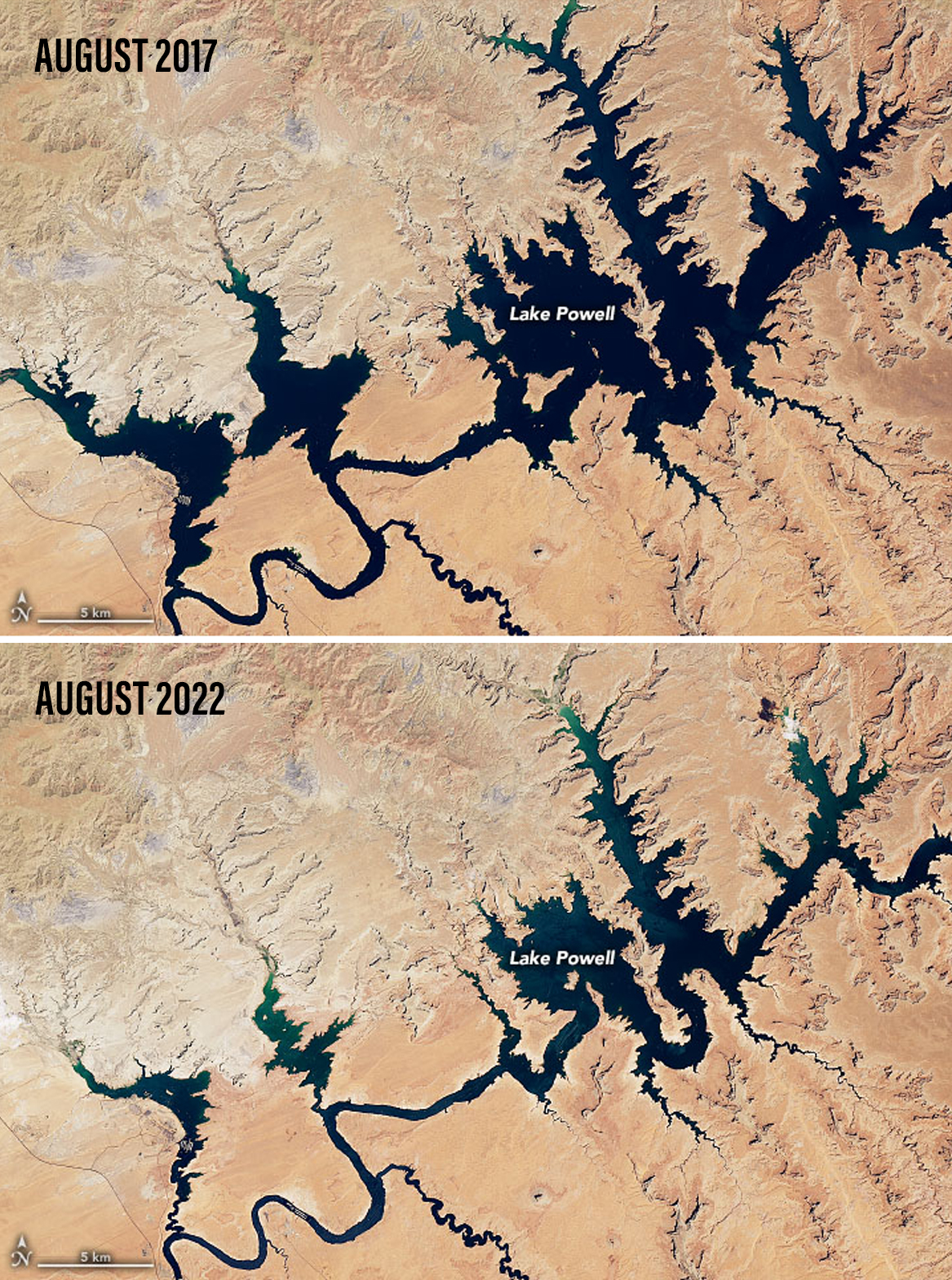

The Colorado River Basin has been experiencing a severe mega-drought for the last two decades, starting around the year 2000. This prolonged dry period, considered one of the worst in the last 1,200 years, has been exacerbated by rising temperatures driven by climate change. The impacts of this mega-drought are evident throughout the Basin, including:

- Declining Reservoir Levels: Due to low inflows coupled with high releases, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two largest reservoirs on the Colorado River, have seen dramatic declines in their water levels, reaching historically low elevations.

- Reduced River Flows: The overall flow of the Colorado River has significantly decreased since 2000, impacting water availability.

- Ecological Stress: Reduced river flows and warmer water temperatures have impacted aquatic ecosystems, threatening native fish species and riparian habitats, and benefiting invasive species.

- Increased Wildfire Risk: Drier conditions have contributed to a significant increase in the frequency and intensity of wildfires across the Basin, stressing natural water systems and affecting runoff.

Satellite images of Lake Powell showing water level decline since 2017

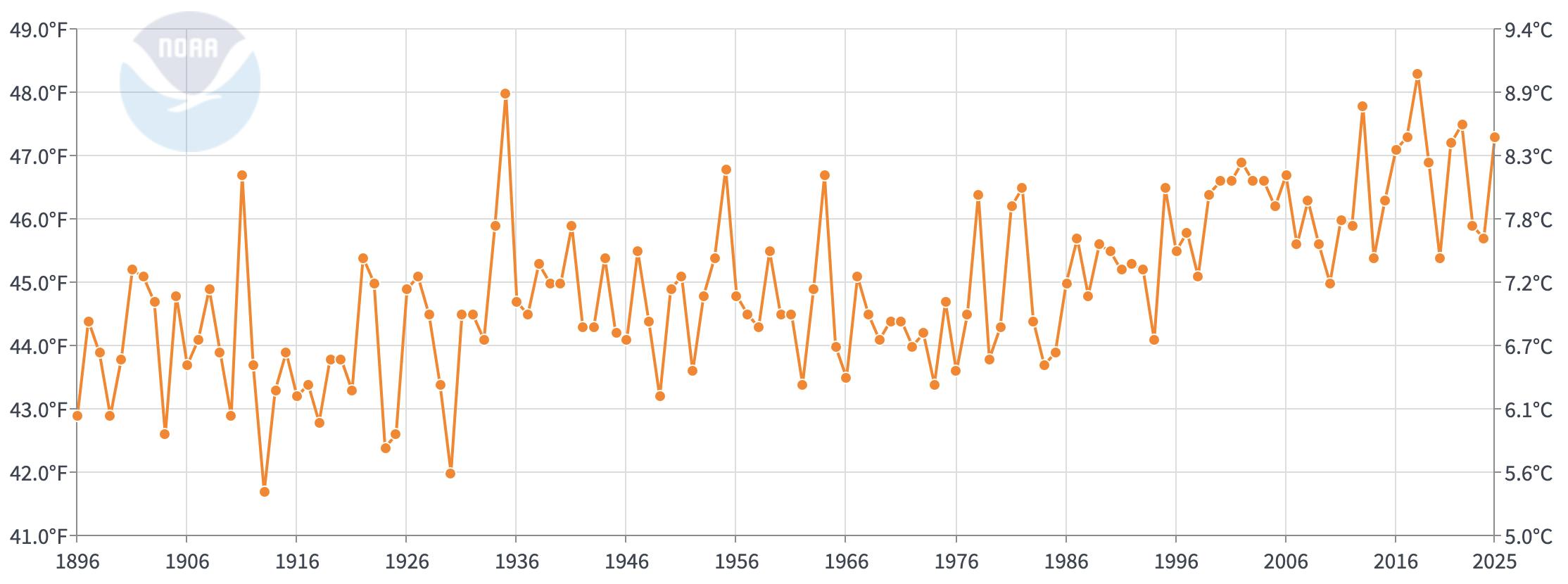

Warming in the Upper Basin

The Upper Basin has been significantly affected by climate change. For example, over the last 120 years, records indicate that Colorado’s average temperature has increased by approximately 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit. This warming trend has accelerated in recent decades, with the five hottest summers on record occurring since the year 2000.

This pronounced warming in the headwaters of the Colorado River directly contributes to the challenges faced throughout the entire Basin by reducing snowpack, increasing evaporation, and altering the timing of runoff. The hotter summers also increase demand for water for irrigation and municipal uses.